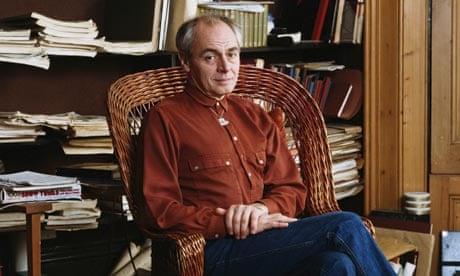

R.D. Laing, a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, worked in a relentless rebellion against the psychiatry and psychotherapy establishment.

A few words about his life:

He was born in Glasgow and studied medicine at the university there, then he specialized in psychiatry and psychotherapy. He worked as a psychiatrist in Glasgow from 1953 to 1956. In 1957 he moved to London. He became famous that year with the publication of his first book, The Divided Self, in which he gave voice to a theory that sees mental disturbance as a result of social or family influence. After that he continued to write books relating to existential philosophy. Among his books:

The Politics of Experience (1967)

Knots (1970)

The Politics of the Family (1976)

Sonnets (1980)

The Voice of Experience (1982)

After his studies, he was drafted into the army. He served as a psychiatrist, then left the army in 1965, and established Kingsley Hall in East London. This was an alternative to a mental hospital, and it was run as an equal treatment community, without rules or force. Kingsley Hall was closed because of complaints, but groups of his students continue to run such houses in Britain.

His personal tragedy was that he began his career as a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, meaning that he was supposed to bring healing or improvement to the client’s state. But after he was qualified, he seems to have discovered that in his soul he was an existential philosopher, a rebel, with a revisionary theory about the state of society and the state of the human soul.

His identity as philosophical rebel stood in opposition to the essence of therapy, because to be a therapist is to return the client to normal social function, whereas the philosopher does not try to correct, only to reflect.

That means that there was a strong contradiction between his personal mission (existential philosophy) and his professional role. It could be said that Laing the psychotherapist contradicted Laing the existential philosopher, and the other way around. Incidentally, he wasn’t the only psychologist that was, at base, a philosopher. Two others were Erich Fromm and Victor Frankl.

But he wasn’t just another thinker. He was a rebellious, bold and brilliant thinker. He knew no boundaries in his rebellion. He kept going until the end, with his radical accusation of the psychiatric establishment.

He was a representative and a voice for what he saw as the poor mentally ill, who received hardly any humanity from the psychiatric establishment.

He came out with the truth burning inside him, but he was perceived as blunt, bold and provocative.

He rebelled, but was naive enough to think that his rebellion would yield results, but this did not happen. Thus, the more he wrote and lectured, the more he was relegated to the periphery and was treated as an anecdote. And, moreover, two years before his death he was thrown off the British medical register (he was caught with cannabis in his possession).

He died in France, during a tennis match, from a heart attack. At that time, he was married for the third time, an alcoholic vegetarian, practicing yoga, and suffering from recurring depressions.

His theory:

Well, it is possible to sum up his main principles in the words of Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence. He claimed that Laing believed that modern society surrounds the individual with walls of adjustment and conformity that inhibit potential and selfhood. In Laing’s opinion, it is possible that what we call madness is really the inability to suppress normal sensibility, to adjust to a society which is not normal.

Laing himself said that he could only work in psychiatry, at all, because he felt greater fraternity with the mentally ill than with those who call themselves sane. He commented that when he was touring mental hospitals, he felt that the residents did not seem to him any more dangerous than most of the staff. As part of his research he compared families of people who suffered from schizophrenia and normal families. He felt, entering the homes of the normal families, as though he was entering a poisonous gas chamber.

Laing thought that what people called life is no more than a quiet death. They are dead inside but behave as if alive, on the outside. In this connection he liked to quote Friedrich Nietzsche: “Your soul will be dead even before your body: fear nothing further.“

Laing on lies and schizophrenia:

According to Laing, saying that all people are in fact robots, zombies, the living dead – a typical claim of schizophrenics – is also a conclusion you could arrive at by right feeling, and, further, it is true. And what is supposed to be a sane and normal conception of life, is simply a wrong conception.

Normal people are not allowed to say things which the insane, or famous artists, can say. Allen Ginsberg, for example: “The only freedom we have is in the cage we have built for our self.” A sane person who said this would be considered deviant.

What emerges is that Laing was a hard, radical critic of the way human beings live. One of the things he was very much against is what he called “a liar-based way of life.” According to him, it is like an infectious disease, because liars have to convince others to believe them. The liars hypnotize other people who are trapped in the web of lies. And if people stop trusting their own sensibility, the ground of reality begins to shake under their feet.

In his words, the freeing of oneself from the liar-chains of others is like jumping into an abyss, when the abyss is total freedom. So we stay in the lies, afraid of the abyss and the freedom. But according to his concept, freedom is not an abyss, but a corridor to the rehabilitation and construction of ourselves.

This had already been said in Escape from Freedom, a book by the Frankfurt-born psychoanalyst Erich Fromm. In this book he explains human behavior as a fearful run from the personal freedom that we don’t know what to do with.

And how does living in an atmosphere of lies influence those who inhabit it?

Well, according to Laing, those who live in this atmosphere and are highly sensitive could develop signs of schizophrenia. According to him, most people live in the field of lies and survive. But the highly sensitive cannot continue and function in a sea of lies, and they develop schizophrenia. This allows them to live in two worlds. Their authentic world they don’t give up. The other world is the world of lies, in which its inhabitants have given up their personal truth for the sake of adjustment to the lying social world.

He does not see the illness as a personal, biological or psychological failure, but as an environmental, social failure, because society’s genetic code is a life of lies, a life the schizophrenic cannot adjust to.

Laing on psychiatry and psychotherapy:

Laing belonged to a movement called anti-psychiatry, which heavily criticized psychiatry. The fathers of this movement were Thomas Szasz, Erving Goffman, Michel Foucault, Theodore Lidz, Silvano Arieti, Franco Basaglia, Dr. Peter Breggin and Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson.

The contribution of Laing to anti-psychiatry is human, concrete, and psychological, while there are those who also contributed to the anti-psychiatry movement but came from different viewpoints. Michel Foucault sees things from above, from the level of cultural-historical process. Thomas Szasz comes to it from the political, legal and moral angles. Goffman comes to it from a sociological point of view. But only Laing came to insanity from a direct human perspective. In fact, he wanted to understand it from within.

He wanted to shift the center of gravity of the explanation of madness, to see it not as an organic phenomenon, but as social. For example, in his book Sanity, Madness and the Family, written with Aaron Esterson, he tries to prove that behavioral disturbances can only be convincingly explained against the background of the social and family framework in which they were molded.

Overall, he had a subversive and rebellious way of seeing, not only mental illness, but also the fear-ridden relationship between the psychiatrist and the psychotic.

He claims that in the area of psychoanalysis there is an amazing happening. Psychoanalysts claim that psychotics don’t live in the real world, but in a world they have distorted for their own needs. And they do this via depersonalization (experiencing the self as unreal), objectification (treating the other as an object), lack of empathy, lack of emotional relationships, projection, reversals (of certain cravings to opposite ones), denial, (ignoring certain characteristics and behavior as though they don’t exist), and so on.

But according to his radical claim this is exactly what some of the psychoanalysts do to their clients. They treat them in the way they claim that their clients behave: they depersonalize them, that is, they treat them in an alienated way, with no personal dimension, as an object should be treated, coldly. According to his claim, psychiatrists approach the client in a non-emotional way, and stick to their cold, rational tools. He adds that they attribute to the patient feelings that they, the therapists, feel but find it difficult to admit to. And so, they pass to the patient their own fears and problems. And thus, the patient becomes a scapegoat. By admitting to shortfalls, a patient allows the therapist to feel “cleaner.”

This claim is probably the most outrageous, rebellious claim that could be directed at the therapeutic establishment: that under cover of treating patients, psychiatrists transfer to them their own anxieties, fears and guilt feelings.

In his books, mainly The Divided Self and The Politics of the Family, Laing objected to the therapeutic approach that studies the patient detachedly. He advocated empathy, relating to the patient’s pains and distresses and through them trying to understand.

There is this true story that describes his empathy for patients:

While still in Chicago, Laing was invited by some doctors to examine a young girl diagnosed as schizophrenic. The girl was locked into a padded cell in a special hospital, and sat there naked. She usually spent the whole day rocking to and fro. The doctors asked Laing for his opinion. What would he do about her? Unexpectedly, Laing stripped off naked himself and entered her cell. There he sat with her, rocking in time to her rhythm. After about twenty minutes she started speaking, something she had not done for several months. The doctors were amazed. ‘Did it never occur to you to do that?’ Laing commented to them later, with feigned innocence.

John Clay, R.D. Laing: A Divided Self. (pp. 170-171)

In 1969, in his book The Politics of the Family, Laing specifies how the family distorts the ways of thinking and behavior of its members and creates conformity among them, even if the price is the mental illness of the weaker and more sensitive member of the family.

And so, Laing is portrayed as one of the greatest rebels in one of the most sacred establishments in the 20th century. And against what is he actually rebelling?

Well, first of all he is rebelling against the exclusive authority of the psychiatric establishment on the human psyche, and secondly, he is rebelling against the tradition that sees and relates to psychotic situations in a cold and alienated way, treating the patient as an object.

Laing claims that Freud relates to neurosis only after he has frozen, analyzed, sterilized, and categorized it. Laing thinks that we must learn to relate to mental disturbance as something alive, a living part of the human, and not after it has become an object in the intellectual laboratory.

He doesn’t dismiss Freud, only the lack of humanity in his approach. Laing claims that patients are asking for help because they feel like broken objects. And it is exactly the psychiatric approach that causes them to feel even less intimate with and close to themselves. They become “frozen” by the psychiatric approach.

Laing on schizophrenia:

Laing’s specialty was schizophrenia and schizophrenics, and his first big book The Divided Self was on this subject. He saw the process of turning a person into a schizophrenic as a process that begins by the insistence of society on behavior which is only clean and positive. This is a behavior which doesn’t allow the “dark self” to come into expression. Schizophrenics do not possess the ability to repress the “dark self.” Therefore, they feel an ontological insecurity, that something in them is not right. They believe no one else has this feeling.

And so, they feel different, that they are not part of the social world around them. And then, instead of wearing a mask and killing the inner self (like everyone else), they divide themselves into the false self which is presented to the world, and the authentic self, not presented to the world.

Here Laing’s work connects to that of Paul Tillich and Rollo May.

The implication is that this dividing of the two selves is to lower the threshold of anxiety. Laing found out that presenting our true self to society involves an existential anxiety about society’s expectations, about getting a negative response (maybe we do not fit, are not acceptable). So as to decrease the anxiety, schizophrenics eliminate exposure of the authentic self. If the false self is rejected, it will not be so bad because they will feel less pain. So schizophrenia, according to Laing, is an extreme response of a highly sensitive and authentic person to social pressure.

People confront, in his view, two options: A. to give up their authentic self. B. to rebel. But schizophrenics choose a middle option: to keep their authenticity and at the same time to adopt a false self for society.

And all this contrasts with people defined as normal, who avoid the inner self and choose the false self. Schizophrenics, according to Laing, remain stuck between the two, meaning that instead of a conflict between themselves and the social establishment (rebellion), they take the conflict inside. Schizophrenia is the conflict, internally, between the two selves. And then the disturbance is exposed, first in front of the family and then in front of the psychiatrist.

And then, Laing says, the horror begins. The moment the disturbance is exposed, instead of empathy, schizophrenics get a label: something is wrong with them. Their role is the role of drainpipe, scapegoat. And then, the disturbance intensifies.

There is no doubt that this is an extremely radical accusation.

——————————————–

Sayings:

Long before a thermonuclear war can come about, we have had to lay waste to our own sanity. We begin with the children. It is imperative to catch them in time.

Without the most thorough and rapid brain-washing their dirty minds would see through our dirty tricks. Children are not yet fools, but we shall turn them into imbeciles like ourselves, with high I.Q.s if possible.

(Laing, R.D. 1990a. The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise. London: Penguin

Books Ltd: p.49)

A little girl of seventeen in a mental hospital told me she was terrified because the Atom Bomb was inside her. That is a delusion. The statesmen of the world who boast and threaten that they have Doomsday weapons are far more dangerous, and far more estranged from ‘reality’ than many of the people on whom the label ‘psychotic’ is affixed.

(Laing, R.D. 1990b. The Divided Self. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

: 12)

We are living in an age in which the ground is shifting and the foundations are shaking. I cannot answer for other times and places. Perhaps it has always been so. We know it is true today.

(Books Ltd: p. 108)

They are playing a game. They are playing at not playing a game. If I show them I see they are, I shall break the rules and they will punish me. I must play their game, of not seeing I see the game.

(Laing, R. D. 1974. Knots. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

: p. 1)

Top heavy apparatus of psychodynamics and cognitive psychology is at worst a fantasy and at best a metaphor.

Rom Harre 04.11.98

What we call ‘normal’ is a product of repression, denial, splitting, projection, introjection and other forms of destructive action on experience. It is radically estranged from the structure of being. The more one sees this, the more senseless it is to continue with generalized descriptions of supposedly specifically schizoid, schizophrenic, hysterical ‘mechanisms.’ There are forms of alienation that are relatively strange to statistically ‘normal’ forms of alienation. The ‘normally’ alienated person, by reason of the fact that he acts more or less like everyone else, is taken to be sane. Other forms of alienation that are out of step with the prevailing state of alienation are those that are labeled by the ‘formal’ majority as bad or mad.

R. D. Laing, The Politics of Experience

——————————————————————————————————

John Clay’s book: R.D. Laing: A Divided Self. (pp. 170-171)